In the age of sensational blockbuster exhibitions it’s fairly unusual to find one that is wholly dedicated to a single artistic technique, rather than a single artist or movement. So this quiet exhibition hidden away on the top floor (but one) of the British Museum was a real joy to find. Drawing in Silver and Gold tracks the rise of metalpoint drawing from its early beginnings in the medieval illuminated manuscripts, through its post-Renaissance decline, to its understated resurgence in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Benozzo Gozzoli, A nude man holding a rearing horse, c. 1447-1449. Silverpoint, grey-black wash, heightened with white, on blue prepared paper. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum.

Metalpoint drawing involves a metal stylus, usually tipped with either silver or gold, which is applied to paper with a prepared ground, the abrasiveness of which causes some of the metal to be left behind; the result is a medium which allows for pinpoint precision and rapid execution, maximising the potential for expression and experimentation. The early Renaissance artists seized upon this, producing studies and sketches of heads, torsos and limbs which often had an astonishing naturalism and freshness, and even sometimes drawings which look as though they could have been made in the 20th century rather than the 15th. Leonardo features heavily in this exhibition, unsurprisingly, and indeed some of his drawings are truly exquisite, almost divine in their shimmering aspect: his famous Hands study opens the exhibition, and one of the star pieces has to be his extraordinary Head of a Warrior with the craggy face and exceptional level of detail around his lion-topped helmet. However, for me it was the exquisite drawings by his less popularised contemporaries that were the true revelations.

Lorenzo di Credi, Head of a boy, c.1485-1495. Metalpoint (probably silverpoint) heightened with white, on light brown paper. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum

Benozzo Gozzoli’s Nude Man Standing with a Rearing Horse is set on a blue-grey wash, the metalpoint barely visible, and the form itself picked out in white heightening, so that the dramatic figures look like constellations set against a deep night sky; Lorenzo di Credi exploited metalpoint’s potential for detail in his Head of a Boy study, which picks out in stunning detail the boy’s lips, eyes and nose in the most delicate lines, creating a kind of poignant ode to youth; Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio’s study of drapery for a painting of the Risen Christ perfectly mimics the crispness of stiff fabric.

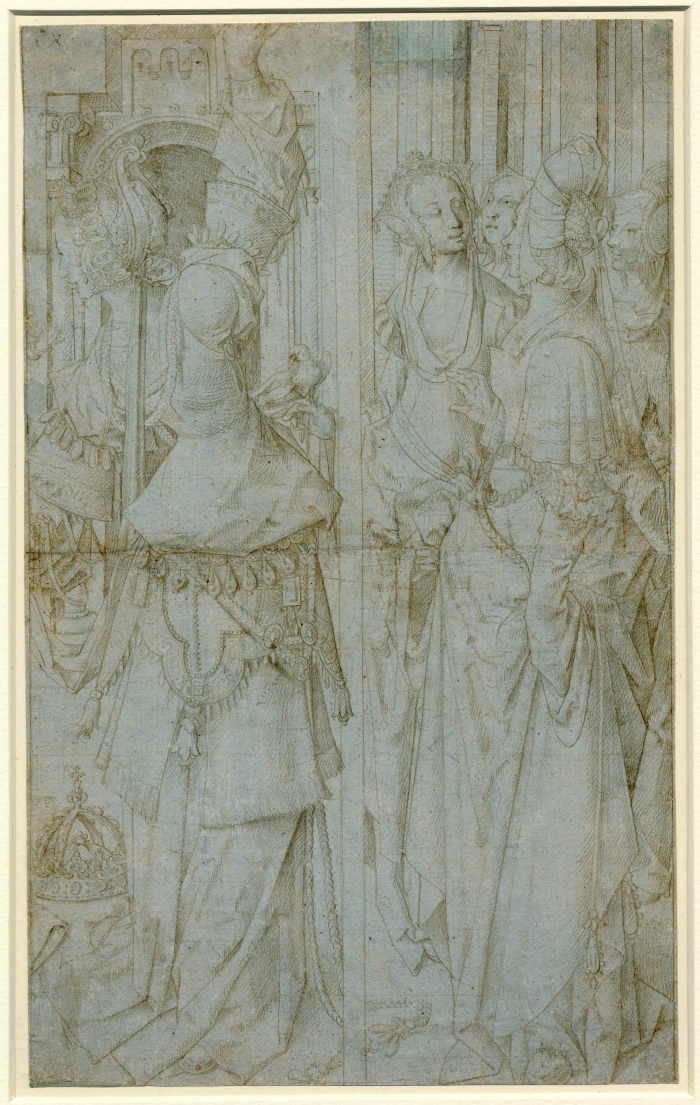

Above: Study of Christ’s drapery rising from the tomb, c. 1491. Black chalk and silverpoint, heightened with white, on blue prepared paper. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum. Below: Anonymous Netherlandish, Augustus and the Tiburtine sibyl, fragment of a design for stained glass, c. 1520s. Silverpoint on pale blue prepared paper. Copryright Trustees of the British Museum.

The main point of interest in the exhibition was its comparison of the way Renaissance artists across the differing European schools used metalpoint – early Netherlandish drawings demonstrate how it was often used much more for drawings after paintings rather than preparatory studies for them, and they don’t really have the immediacy and freshness of the Italian school. However, as we move to the great portraitists of the Northern Schools – Rogier van der Weyden and Hans Holbein the Elder – we see the medium being used to its best advantage. Van der Weyden’s Young Woman has an intense gaze, whilst Holbein’s Woman Wearing a Headdress is amazingly lifelike, and his Portrait of the banker Jakob Fugger feels forcefully realistic, unlike the idealised heads of the Italians. The absolute star of the show though, is Dürer’s Head of a Boy, inclined to the left: astonishingly contemporary looking, in both expression and pose, as the boy cocks his head curiously (or is it resignedly)- and the clarity of line.

Rogier van der Weyden, Portrait of an unknown young woman, c.1435-1440. Silverpoint on cream prepared paper. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum

Albrecht Durer, Head of boy, inclined to the left, c. 1505-1507. Silverpoint with pen and brown ink, heightened with white, on grey-cream prepared paper. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum.

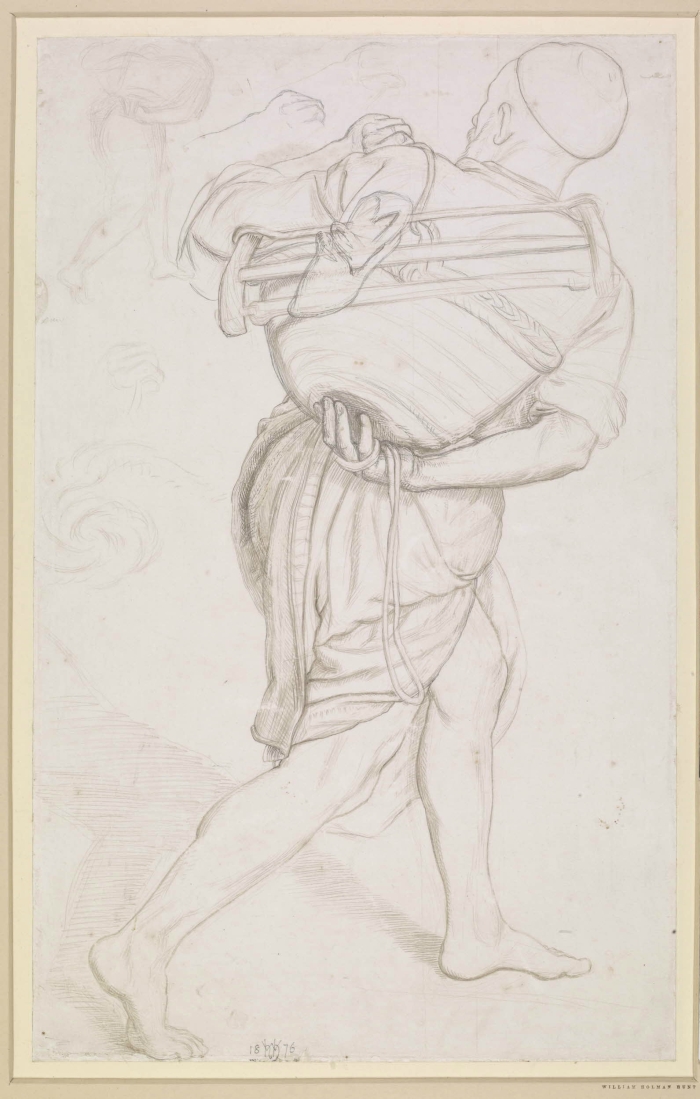

Next to all of this this, the revival of the medium in the 19th and 20th centuries seems like a rather insignificant post-script, although there are a couple of beautiful drawings here, such as Holman Hunt’s Study for St. Joseph, with its strongly graphic, almost Michaelangelo-esque use of line, demonstrating how the Pre-Raphaelites and Nazarenes sought to emulate early renaissance artists in every aspect of their practice. The exhibition closes today, but if you’re in central London and I would strongly advise popping in – you only need an hour, but those faces may stay with you forever.

William Holman Hunt, Stdy for St Joseph, 1876. Silverpoint with graphite and scraping, on white prepared paper. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum.